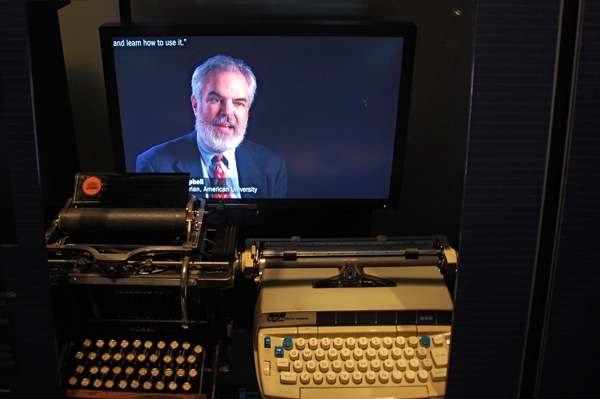

American University professor W. Joseph Campbell, featured in a video at the Newseum in Washington.

Jack Shafer, a prominent media critic for the online magazine Slate, said in a post this week that yellow journalism, an antiquated practice that often rubbed people the wrong way but got things done, merits consideration for a modern resurgence.

Bring Back Yellow JournalismOn the verge of the 20th century, a sort of advocacy newspapering aggressively sought solutions to the plight of the common man - the underdog - and investigated shady practices. Additionally, yellow journalism played up topics such as crime, scandal, gossip, divorce, sex and disaster - sound familiar? - that could be considered sensational to the higher-brow publications these days. But politics and business were parts of the coverage, too, establishing appeal across the demographic.

At its best, it was terrific. At its worst, it wasn't that bad.

By Jack Shafer

Posted Monday, March 30, 2009, at 7:32 PM ET

Because of its name and its topical matter, yellow journalism is not the most endearing of newspaper genres to modern-day reporters and editors. Bloggers, paparazzi and some tabloids are a different story. But the meat of Shafer's writing is that yellow journalism wasn't so awful in the first place. And I agree with the media critic's premise - not just because he gives good press to a former professor of mine.

To back up his thoughts, Shafer uses the books of W. Joseph Campbell (left), a journalism professor who was my work-study supervisor at American University. His "Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies" dispels some of the misconceptions of yellow journalism.

To back up his thoughts, Shafer uses the books of W. Joseph Campbell (left), a journalism professor who was my work-study supervisor at American University. His "Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies" dispels some of the misconceptions of yellow journalism.In a time of great upheaval in the newspaper industry, any idea is worth consideration. On the other hand, many theories that have been afforded considerable thought and action recently have not panned out. We already have seen two large metropolitan newspapers, the Rocky Mountain News and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, close this year. We are nearing that we've-got-nothing-to-lose point.

In spite of their wounded state, newspapers still have power. They are widely read - online and in print - and are even trusted at times. And amid economic turmoil, those common people who were once taken under the wing of yellow journals again need an ally among the giants. Shafer writes, "Campbell's revisionist view doesn't downplay the activist nature of the yellow journals, which would set up soup kitchens, send relief to victims of hurricanes [and] file lawsuits to get government contracts overturned."

Shafer does not present the idea that yellow journalism would be successful or at least useful in contemporary times. He fails to address the economy and how it has victimized those common people. He does mention, as does Campbell, that today's civic journalism bears some resemblance to the yellow variety, but that it stops short of action.

To take it one step further than just saying yellow journalism wasn't all that bad, you would have to consider how it might work in the current climate.

Many Americans wouldn't mind having an advocate fighting for them against powerful corporations and government bureaucracies. Reporting before the Iraq war and the current recession was lacking. There were hints of what was to come. Newspapers didn't do enough to pick them up and point them out. Aggressiveness and action, trademarks of yellow journalism, were missing.

In many ways - through the strict teaching of journalism schools and the codes of ethics developed by media outlets - journalists today cling too closely to ideals. They're afraid of taking sides, even when the right, moral one is clear. I am bound to such principles in my job as a copy editor. I was taught them and told to adhere to them throughout nearly six years of journalism education.

Reverting to yellow journalism, therefore, might be considered ethically compromising. But at the same time, it would be a reversion to common sense, a jettisoning of media elitism and a return to the all-out battle for truth, justice and the American way.

Common people need their superhero in the media.

More: Prominent among the myths in Campbell's aforementioned book is yellow journalism trailblazer William Randolph Hearst's alleged quote, "You furnish the pictures, and I'll furnish the war." Campbell will expound on that and other media myths in his upcoming book. He'll also include a chapter on the case of Army Pfc. Jessica Lynch. I contributed to that research, and you can see my findings here.

[HEADSHOT COURTESY OF WJOSEPHCAMPBELL.COM]

1 comment:

Interesting points. I read Shafer's article, but as you said, it's hard to even consider a return to this type of journalism given the lessons we've been taught over the years.

One of my professors used to rant about how advocacy journalism is the way to go. He used a small local newspaper targeted toward Hispanics as an example of a successful model. But I think that illustrates that advocacy journalism almost requires a smaller community as an audience, one which the staff of the news organization knows well. That concept of getting in touch with your audience, knowing what they want, seems almost lost on most news organizations these days, so I'd be hesitant to trust their implementation of advocacy on the part of this community.

Also, no matter how close we get to that "nothing-to-lose point," the one thing we cannot afford to give up is credibility. Of course, it seems like an "all-out battle for the truth" should increase that credibility, right?

Post a Comment